A Mysterious Anomaly May Be Amelia Earhart’s Plane. This Team Is Racing to Prove It.

Here’s what you’ll learn when you read this story:

Purdue University announced a plan to locate Amelia Earhart’s lost aircraft.

Dubbed the Taraia Object Expedition, the effort will include a field team visiting the Pacific island Nikumaroro in November 2025.

The goal is to “close the case” on Amelia Earhart’s disappearance on July 2, 1937.

This story is a collaboration with Biography.com.

Exactly 88 years after Amelia Earhart vanished over the Pacific Ocean, Purdue University—which helped fund her historic attempt to fly around the world—has announced it will lead a new effort to solve aviation’s greatest mystery. The university has detailed plans to search a remote island where many believe Earhart’s plane may have crashed on July 2, 1937.

In November 2025, a field team from the Purdue Research Foundation and Archaeological Legacy Institute (ALL) will head to the island of Nikumaroro to confirm whether the long-debated Taraia Object, an anomaly at the site halfway between Australia and Hawaii, really is the Lockheed Electra 10E plane once piloted by Earhart.

“With such a great amount of very strong evidence, we feel we have no choice but to move forward and hopefully return with proof,” Richard Pettigrew, ALI’s executive director, said in a statement. “I look forward to collaborating with Purdue Research Foundation in writing the final chapter in Amelia Earhart’s remarkable life story.”

Photo credit: Hearst Owned

Photo credit: Hearst OwnedGet the Issue

Photo credit: Hearst Owned

Photo credit: Hearst OwnedGet the Issue

Photo credit: Hearst Owned

Photo credit: Hearst OwnedGet the Issue

Photo credit: Hearst Owned

Photo credit: Hearst Owned Get the Issue

Photo credit: Hearst Owned

Photo credit: Hearst OwnedGet the Issue

Photo credit: Hearst Owned

Photo credit: Hearst OwnedGet the Issue

Photo credit: Hearst Owned

Photo credit: Hearst OwnedGet the Issue

Photo credit: Hearst Owned

Photo credit: Hearst Owned Get the Issue

Photo credit: Hearst Owned

Photo credit: Hearst OwnedGet the Issue

This latest effort joins a long list of attempts to finally solve the Earhart mystery. According to Pettigrew, the Taraia Object hypothesis draws on a mix of documentary records, photographs, satellite imagery, physical evidence, and eyewitness accounts.

Several key pieces of evidence are driving the latest push. These include:

Radio bearings recorded form radio transmissions at the time by the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Coast Guard, and Pan American World Airways, which converge on Nikumaroro

A 2017 analysis of human bones discovered on the island in 1940, which determined Earhart’s bone lengths were more similar to the discovered bones than 99 percent of individuals

Artifacts of a women’s shoe, a compact case, a freckle cream jar, and a medicine vial, all dating to the 1930s

A photographic anomaly—called the Bevington Object—captured three months after the plane’s disappearance that resembles Electra landing gear on the Nikumaroro reef

And the Taraia Object itself, located in 2020, which has been in the same place in the lagoon since 1938.

The theory suggests that Earhart didn’t crash into the ocean, but instead landed on the uninhabited island—where she was stranded and eventually died.

The new expedition plans to leave the Marshall Islands on November 5 and spend five days on Nikumaroro inspecting the Taraia Object. If successful, the team expects to later excavate Earhart’s lost plane.

Amelia Earhart’s Connection to Purdue University

Edward Elliott, who was Purdue’s president from 1922 to 1945, brought Amelia Earhart to campus as a career counselor for women, and had her live in the women’s residence hall for part of each semester. During her time at Purdue, Earhart also advised the aeronautical engineering department and used the university’s new airport, which was the only one of its kind at a U.S. college or university at the time.

“About nine decades ago Amelia Earhart was recruited to Purdue, and the university president later worked with her to prepare an aircraft for her historic flight around the world,” Mung Chiang, Purdue’s current president, said in a statement. “Today, as a team of experts try again to locate the plane, the Boilermaker spirit of exploration lives on.”

Purdue played a pivotal role in helping Earhart attempt to circumnavigate the globe with navigator Fred Noonan. The university helped fund her Lockheed Electra 10E through the Amelia Earhart Fund for Aeronautical Research, with Purdue trustee David Ross leading the effort alongside major contributors like J.K. Lilly, Vincent Bendix, Western Electric, and the Goodrich and Goodyear companies.

As a thank you for the support, Earhart planned to donate the plane to Purdue upon her return, hoping it would help further scientific research in aeronautics.

Earhart’s connection to Purdue has continued long after her disappearance. Most recently, in 2024, construction began on the roughly 10,000-square-foot Amelia Earhart Terminal at Purdue University Airport.

“Both Earhart and her husband and manager, George Putnam, expressed their intention to return the Electra to Purdue after her historic flight,” Steven Schulz, senior vice president and general counsel of Purdue University, said in a statement. “Based on the evidence, we agree with ALI that this expedition offers the best chance not only to solve perhaps the greatest mystery of the 20th century, but also to fulfill Amelia’s wishes and bring the Electra home.”

Strong Skepticism

Finding Earhart’s plane won’t be easy, especially since others have searched the site many times before. Ric Gillespie, executive director of the International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) has traveled for a dozen on-site searches for over three decades.

While he agrees Nikumaroro is likely where Earhart landed before passing, he told NBC that he’s come up empty plenty of times before. “We’ve looked there in that spot, and there’s nothing there,” he said about the Purdue effort. “I understand the desire to find a piece of Amelia Earhart’s airplane. God knows we’ve tried. But the data, the facts, do not support the hypothesis. It’s as simple as that.”

Pettigrew, who has worked on searching for Earhart’s plane for years, said objects continually shift in and out of sand coverage. Gillespie said a plane wouldn’t get covered by sand, but would have gotten buried with coral.

The History of Amelia Earhart

As Biography.com highlights, the mysterious final flight of Amelia Earhart captured the world’s imagination in 1937, just as it continues to today. Earhart and Noonan were six weeks and 20,000 miles into their global journey when they failed to make their scheduled landing at Howland Island, located approximately 1,700 miles southwest of Honolulu.

The 2.5-square-mile island proved difficult for Earhart’s plane to find amidst the vast ocean. There’s no concrete evidence that points to why the plane never made it to the island, or where it went instead.

The absence of definitive proof has given rise to a multitude of theories about the fate of Earhart, Noonan, and their plane.

The most widely accepted theory suggests that Earhart and Noonan simply crashed into the ocean and sank after running out of fuel. Another credible theory posits that the duo landed on the in-question coral reef around Gardner Island, now called Nikumaroro Island, located 350 nautical miles southeast of Howland.

Earhart, a Kansas native, began her ascent to fame in 1922 when she piloted her bright yellow Kinner Airster biplane, “The Canary,” to a then-record height of 14,000 feet for female aviators. By 1923, Earhart had earned her pilot’s license, becoming the 16th woman to do so from the Federation Aeronautique. While financial struggles forced her out of flying, she returned to aviation in 1927.

Then residing in Massachusetts, Earhart jumped at the opportunity to be the first woman to partake in a transatlantic flight. Although just a passenger on the 1928 adventure led by pilot Wilmer “Bill” Stultz, her subsequent book chronicling the experience catapulted her into the spotlight.

Following her initial fame, Earhart embarked on her own pioneering flights. In 1932, she made history as the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic, navigating a nearly 15-hour journey from Newfoundland to Northern Ireland.

She continued to add a series of impressive flights to her global résumé, all culminating in what was to be her most monumental flight of all: an ambitious bid to be the first person, period, to circumnavigate the globe along the equator.

Now, almost 100 years after Earhart first took to the skies, the search to solve the mystery of her final flight on July 2, 1937, isn’t just about locating a lost aircraft. It’s about honoring a legacy that shaped modern aviation.

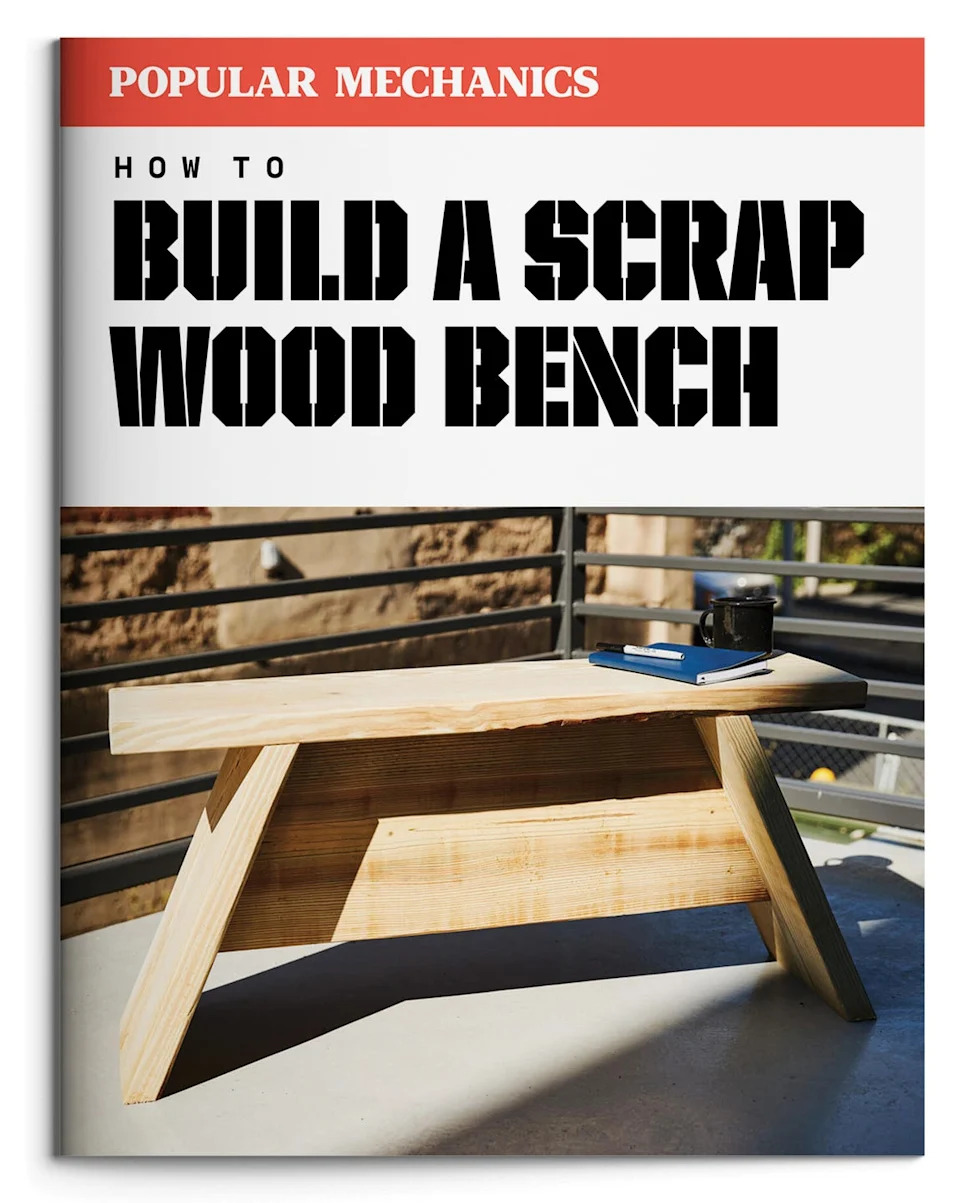

Photo credit: Hearst Owned

Photo credit: Hearst OwnedGet the Guide

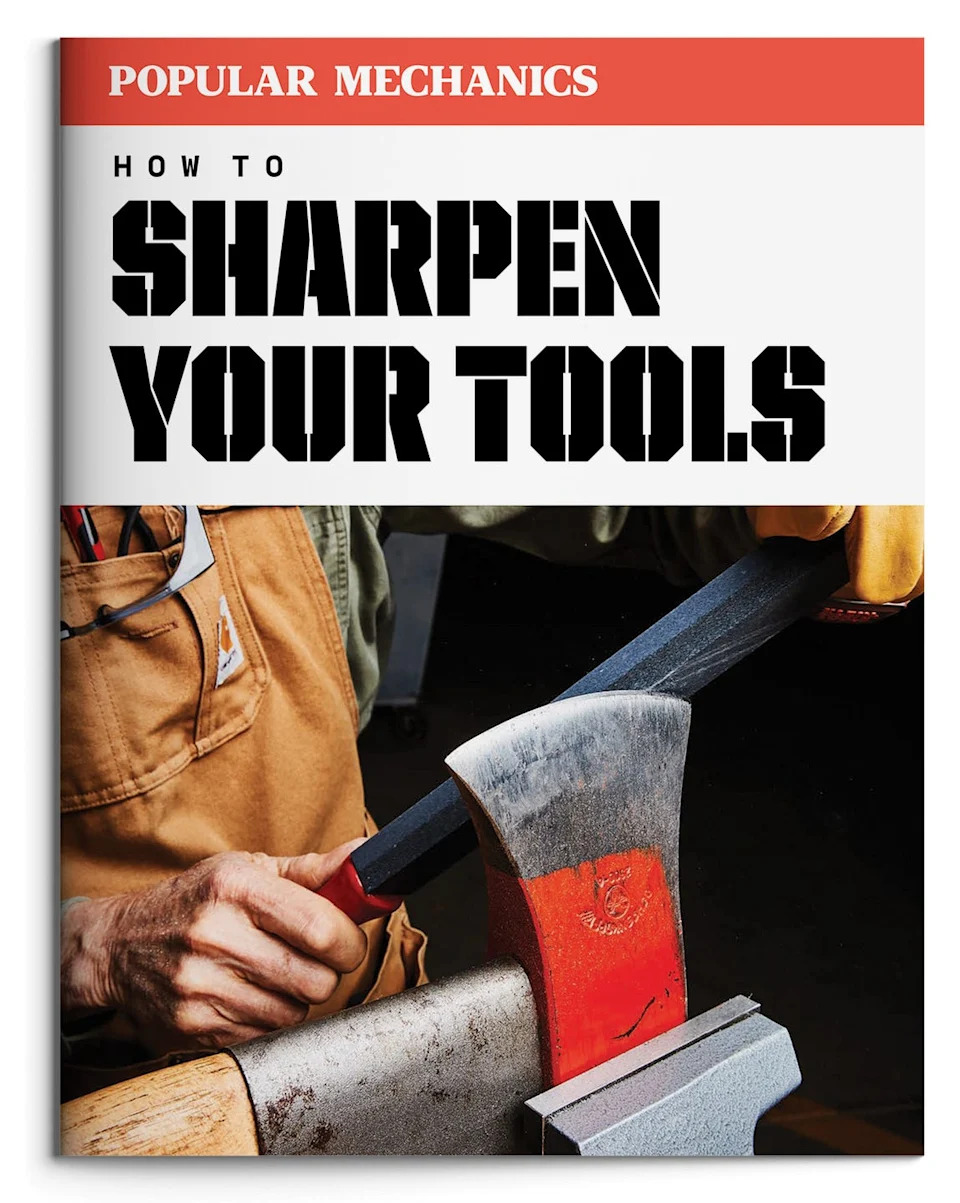

Photo credit: Hearst Owned

Photo credit: Hearst OwnedGet the Guide

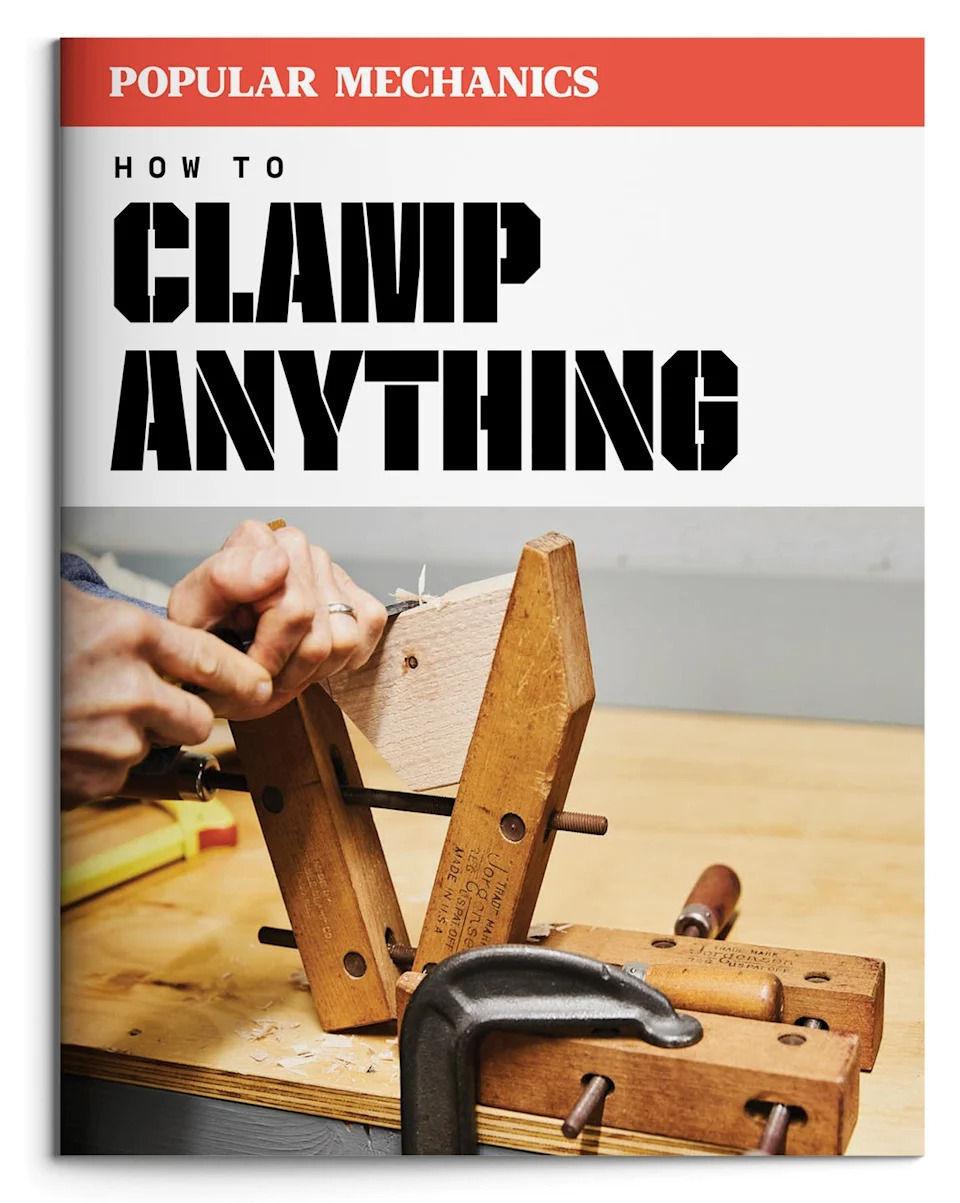

Photo credit: Hearst Owned

Photo credit: Hearst OwnedGet the Guide

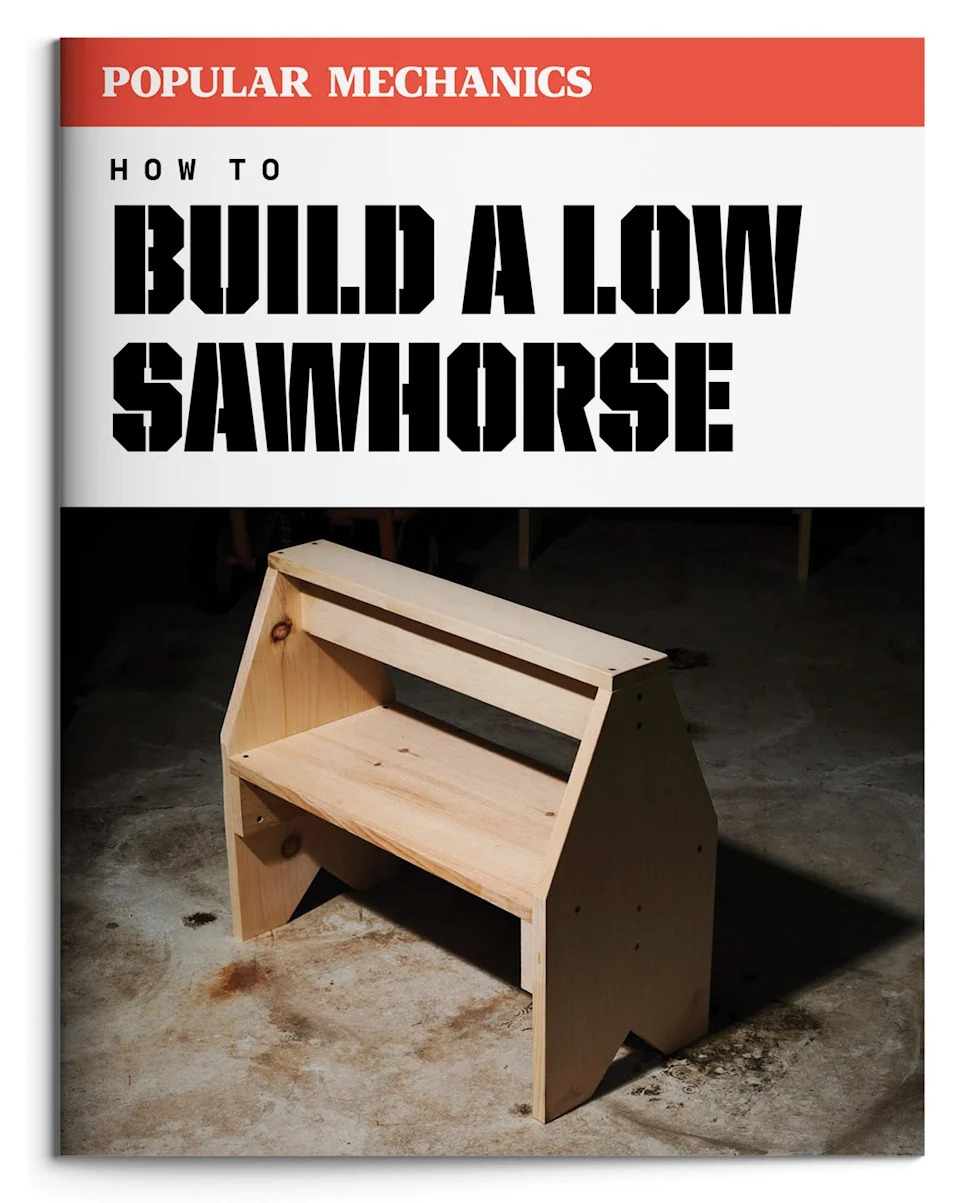

Photo credit: Hearst Owned

Photo credit: Hearst Owned Get the Guide

Photo credit: Hearst Owned

Photo credit: Hearst OwnedGet the Guide

Photo credit: Hearst Owned

Photo credit: Hearst OwnedGet the Guide

Photo credit: Hearst Owned

Photo credit: Hearst OwnedGet the Guide

You Might Also Like

The Do’s and Don’ts of Using Painter’s Tape

The Best Portable BBQ Grills for Cooking Anywhere

Can a Smart Watch Prolong Your Life?