A New Documentary Traces the Gritty Origin of Supreme

Everyone’s heard of Supreme. The name—and the box logo— is almost as recognizable as that of Coca-Cola or Nike. The billion-dollar brand was founded in 1994 by James Jebbia, a quiet, off-the-radar British-American who cut his teeth working at legendary streetwear shop Parachute in Soho before co-founding Union NYC, another early streetwear hub. Now, it’s the label that kids line up around the block for, with merchandise reselling for upwards of six figures depending on the exclusivity of the drop. The brand has collaborated with Louis Vuitton and Damien Hirst. But the origins of Supreme are much more humble and a lot grittier.

In its earliest iteration, it was a small skate shop on Lafayette Street in downtown Manhattan, a place where rebellious kids would meet to connect, chill, cause a little trouble, and skate through the streets. This Supreme story is the one told in ESPN’s latest 30 for 30 documentary, Empire Skate. Directed by Josh Swade, the film traces the history of the label from a store with a staff that wouldn’t help you to a global mega-brand.

When Jebbia opened the shop on a then-desolate stretch of Lafayette, near Prince Street, it was more of a hangout than a retail spot. It was a radical and risky idea at the time—despite the number of city-wide skateboard fanatics in the early 1990s, skate shops were seen as a doomed business model. The brand’s rise to fame came in a completely organic way, when a small group of teenage boys who formed the Supreme crew entered the zeitgeist after being were cast in the iconic film Kids, written by fellow skater Harmony Korine.

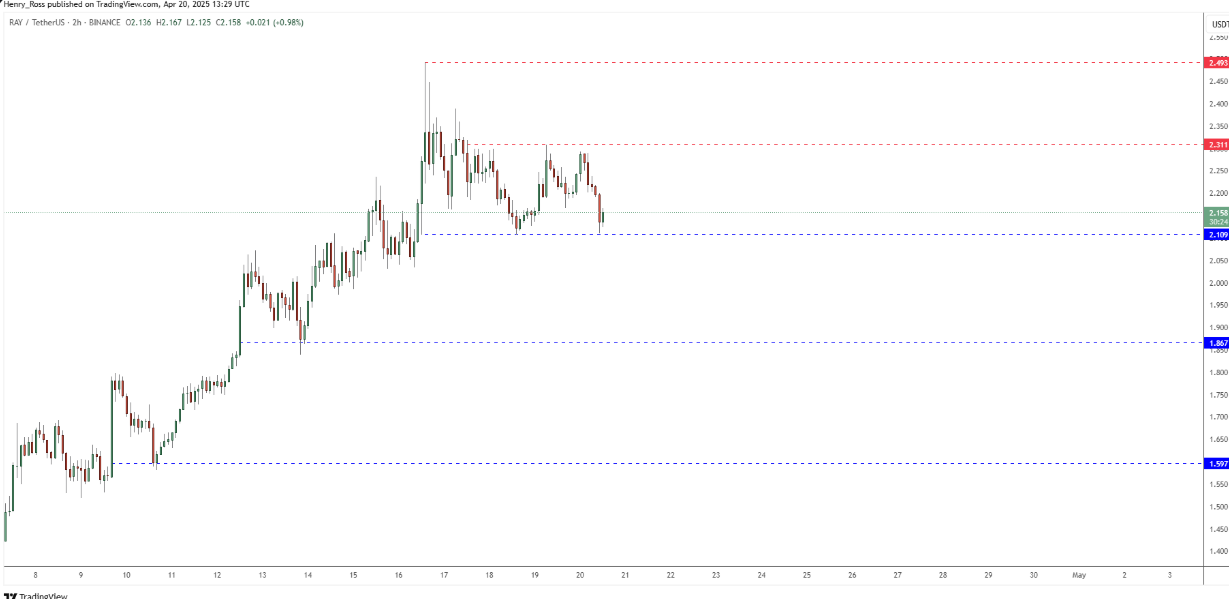

Supreme skaters on Broadway and Astor Place in downtown New York Courtesy of ESPN

Supreme skaters on Broadway and Astor Place in downtown New York Courtesy of ESPNThe crew included those like Peter Bici, Mike Hernandez, Gio Estevez, and Justin Pierce, all of whom “worked” in the shop on Lafayette. Working meant selling t-shirts and boards, sure, but also skating outside, drinking beers in the back room, blasting music in the front, folding t-shirts to Jebbia’s exacting instructions, and often literally telling customers to “fuck off” if they seemed like posers or people who didn’t actually care about the sport of skating. As the Washington Post’s Rachel Tashjian says in the documentary, Supreme was “menacingly New York.” It was also a home for the lost boys of the city and a breeding ground for the kind of unpurified cool marketing executives and social media managers only dream of today.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R16ekkr8lb2m7nfblbH1» iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R26ekkr8lb2m7nfblbH1» iframeThe release of Kids was really the turning point for the Supreme crew and the brand itself, shining an NC-17 spotlight on a subculture that people wanted to be a part of. It’s hard to imagine the original Supreme shop existing in the same way today; in fact, it would be impossible. Walk down Lafayette Street now or in the neighboring streets and you’ll be confronted not by the smell of weed and the sound of kickflips but by matcha lattes and Vuori leggings. The West Village girl would’ve been disgusted by the Supreme boys (and vice versa).

Empire Skate, which premieres on ESPN tonight, is a reminder that real fashion is often bred from communities; it’s born from subcultures that exist on the fringes, not from algorithmic trends and topics. There is nothing cool about a brand telling you what’s cool. Supreme managed to stay hype all these years, but its heartbeat belongs to the kids who ripped it up in that little nothing space on Lafayette. Below, Swade talks about the making of the film and why a group of New York City punks will always reign supreme.

Why were you so eager to make a film about Supreme and its origin story?

I grew up skateboarding. A lot of skaters will say this, but you just can't help but get sucked into that culture. It changes how you see the world, really. I came to New York in the ‘90s and lived downtown. I was intertwined inside this culture and knew a lot of people down there. I was watching everything take shape and watched [Supreme] go from this little shop and this group of skaters that really only had each other, to this thing that became global. I just always felt there was a way to tell the story of this shop with the skaters.

How important is the retail aspect of this story?

The story here in the margins is about retail and the power of brick and mortar. In this day and age, brick and mortar is really struggling. And then you have Amazon. We live in this online world, and you worry that these places of community where kids come together and create culture are going to become a thing of the past. To me, Supreme always felt like a parallel to a shop in the UK, the SEX shop, which Malcolm McLaren and Vivian Westwood started. That was really the home base for, obviously, the Sex Pistols and punk in the UK, but what we came to understand as punk fashion. And without the SEX shop, we don't have a window into that world. There's a documentary called The Filth and the Fury about the Sex Pistols, and that was one of the films that really made me want to do this—in particular, the way those guys came together at that shop.

Why do you think the shop became such a tight-knit and impactful community?

Those people were, in a lot of ways, surviving. There was a sense of desperation there, and that desperation coincided with the way they skated and the way they sort of reseeded and reinvented skateboarding in the '90s. It was a kind of courage and attitude, a kind of not giving a fuck that was all part of the magic. That really does transfer over to why the shop was so enchanting and why these kids in these clothes were things that people wanted to wear and sort of get behind.

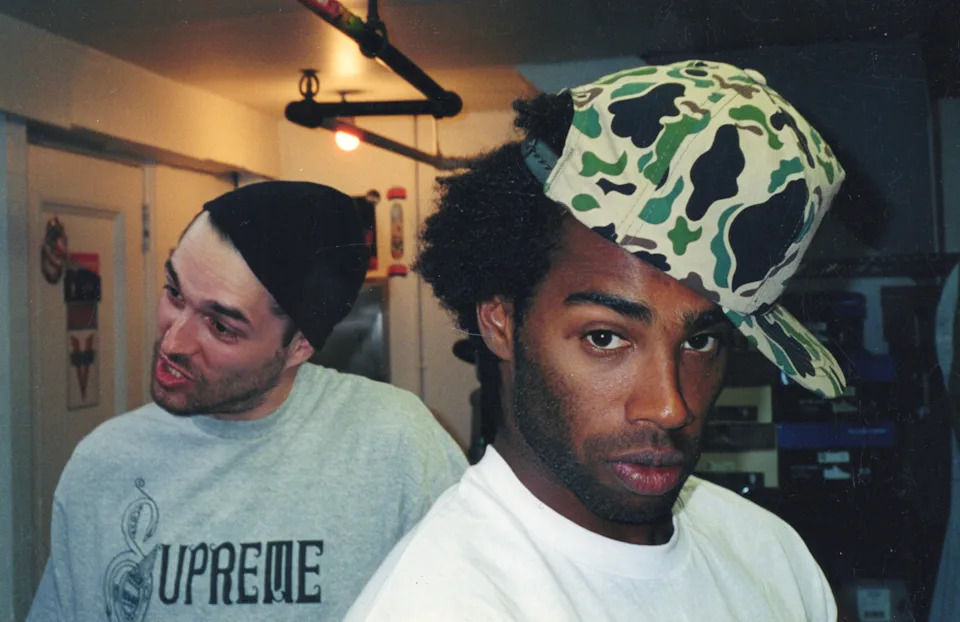

Ryan Hickey (left) and Mike Hernandez in the back room of the Supreme shop on Lafayette Street Courtesy of ESPN

Ryan Hickey (left) and Mike Hernandez in the back room of the Supreme shop on Lafayette Street Courtesy of ESPNKnowing he wasn’t going to be involved in the film, how did you want to approach the topic of Jebbia and the business model he built?

I never felt the need to ask him because everyone said he wouldn't do it, and it really is a story about the kids more than him. I know we have a little sequence in there about him, just to give you some history and sort of explain the myth behind him, but that almost works better than hearing about the business. This really wasn't about what the master plan here was from a business perspective, even though inevitably some of those story beats do come through. It was just always meant to be from the pavement level, if that makes sense.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R1iekkr8lb2m7nfblbH1» iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R2iekkr8lb2m7nfblbH1» iframeAnd listen, the guy is like an absolute—I know we throw this word around a lot these days—genius. Perhaps there was quite a bit of luck and happenstance involved, but you just can't deny what he's built. To me, it's a great American story. It's on the level of Nike, but Supreme never had any luxury cache or celebrity attached to it. Nike had John McEnroe in the early days and eventually, of course, Michael Jordan, but they could trade on endorsements from really visible athletes, guys who were on our television who we watched and celebrated. That's not the same thing with skate, right? So, it's similar to Nike in a lot of ways, but it was also a lot harder to do what he did. What was your first experience with the Supreme store and crew?

By the time I got to New York, I didn't skateboard anymore, but my roommate, who was also from Kansas City, did. And so he was really my introduction to Supreme. I remember going there quite a bit, but I don't really remember the first time. That's a bit of a daze for me, but it was everything we showed in the film. It was so insider that you really had to be there with someone who knew of somebody else, or no one was gonna even look in your direction.

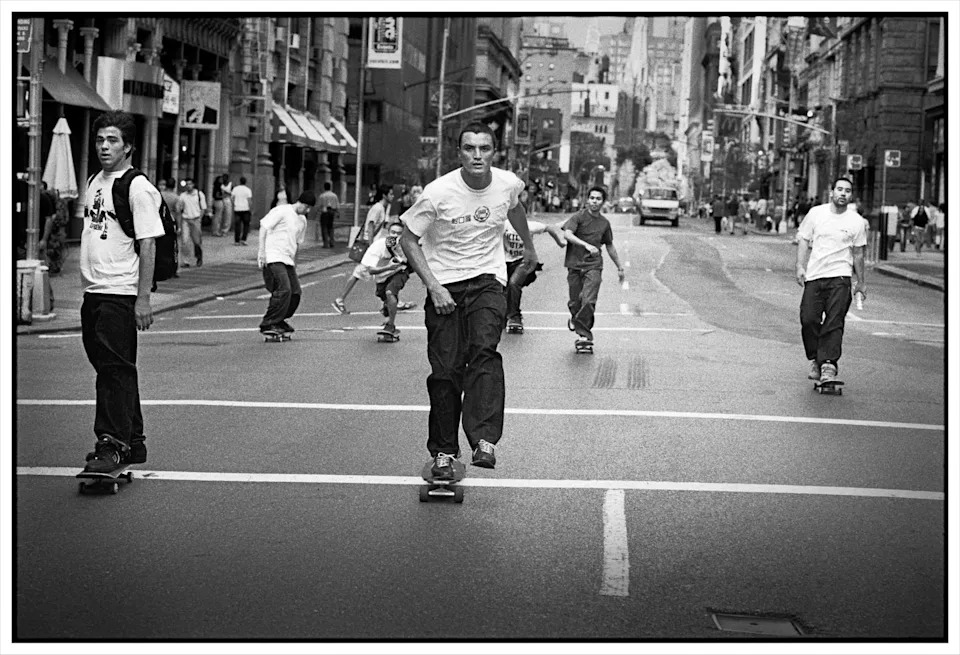

Skaters in downtown New York Courtesy of ESPN

Skaters in downtown New York Courtesy of ESPNWhat was the most surprising thing you learned while making the film?

I found it surprising that all of the guys were ultimately so positive about their experience, long after leaving the shop and the brand. It wasn't like, “Oh, screw those guys. They got big and rich and didn't remember us.” There was none of that. They look back with a lot of fondness and celebration. I was also surprised by my own emotional reaction to filming Peter and Mike when they spoke about becoming firefighters post-Supreme. They talked about having run through their city then, and now they serve their city. That really is, especially given what New York went through with 9/11, very touching. It brought the story full circle, and it’s pretty cool.

You Might Also Like

4 Investment-Worthy Skincare Finds From Sephora

The 17 Best Retinol Creams Worth Adding to Your Skin Care Routine