My life on the road with Oasis, the greatest rock band of the modern age

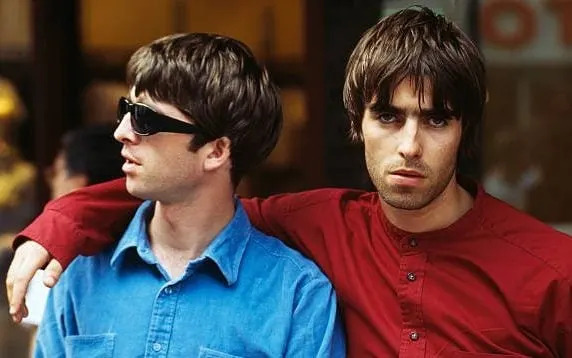

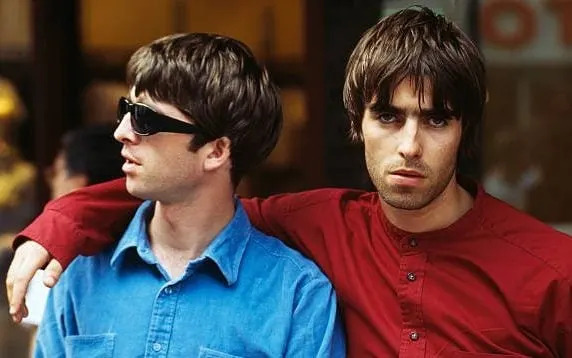

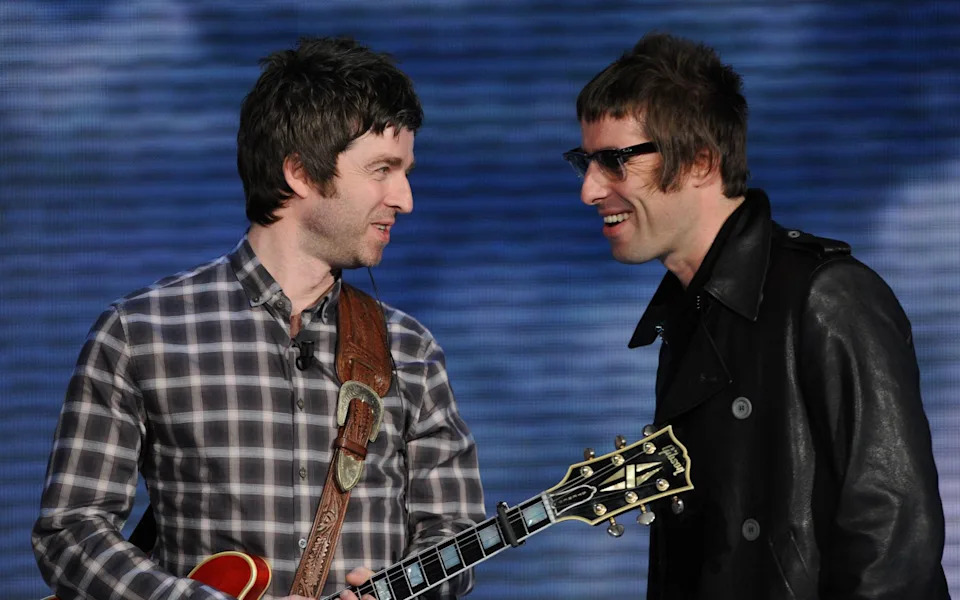

Oh brother: Noel and Liam Gallagher have managed to put their differences aside to reform Oasis - Kevin Cummins/Getty Images

Oh brother: Noel and Liam Gallagher have managed to put their differences aside to reform Oasis - Kevin Cummins/Getty ImagesOne weekend in August 1996, a quarter of a million fans gathered in the grounds of Knebworth House, Hertfordshire, to crown Oasis as rulers of Cool Britannia. Drums thundered, guitars rang out, strings soared and horns blasted through climactic anthem Champagne Supernova, whilst songwriter Noel Gallagher beamed in smug satisfaction and the bug-eyed figure of his onerous sibling Liam Gallagher spread his arms wide and roared “Where were you when we were getting high?”

Well, I know exactly where I was. I was standing deep in the heart of that crowd, with my arm over the shoulder of my own brother, singing along at the top of my voice.

As I wrote in the Telegraph at the time: “Great earthshaking, groundbreaking, world-beating rock and roll occurs at a point where the expression of an artist and the needs of the audience coincide. Right now, this is where Oasis stand.”

Later, when the band had been helicoptered away to continue fighting, cursing, slurping and snorting at their leisure, their audience were left to shuffle painfully towards the exits. For three hours, packed in bomber jackets and bucket hats, we barely moved. Yet all that time, we kept our spirits high by singing Don’t Look Back in Anger, Wonderwall and Live Forever.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R27ekkr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R47ekkr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframeAnd now we are about to do it all again.

Britain has produced many gold-standard rock bands, and I would cite The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Who, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Queen and The Clash as the greatest of all time. To that pantheon we must add Oasis, the outstanding British rock band of the modern age.

I know there will be scepticism about such a proclamation, although not amongst the 14 million people who desperately scrambled to buy tickets when the reunion was announced, or the two million set to attend 40 shows of a world tour that kicks off at Cardiff’s Principality stadium on July 4.

We all know what we are going to get, and it is nothing fancy. Oasis perform as if showmanship is beneath them. They stand still, battering out songs with thunderous drums, fuzzy guitars and barely a hint of musical nuance. Liam spits out lyrics as if he is ready to take on the whole world in a fight. Noel’s elegantly rising and falling melodies do the rest, inspiring the biggest communal sing-alongs you could ever hope to hear.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R2dekkr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R4dekkr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframe“You can’t argue with a good tune, man,” as Noel once told me. Oasis songs are absurdly catchy, bristling with earworm hooks and snappy lyrics performed with total commitment, putting melody at the heart of hard rock. It is like hearing a whole history of British rock in three-minute bursts, the power of Led Zeppelin playing Beatles songs with swagger of The Rolling Stones. “I’ve never been interested in pushing music forward,” according to Noel. “Life is so chaotic in Oasis anyway, I don’t want to be experimenting as well. ‘Let’s try this in an urban cyber-sonic punk style.’ No, give us that Marshall stack and that guitar, I know where I am, thank you very much.”

When Oasis signed to Creation Records in 1993, Noel had one question for the label: “We’re going to be the biggest band in the world. Can you handle it?”

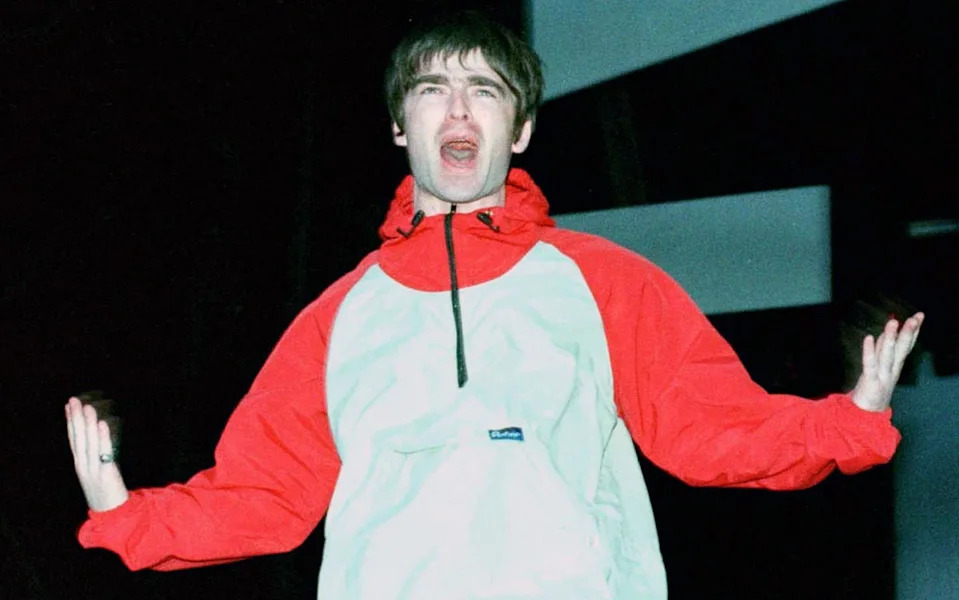

‘We’re going to be the biggest band in the world. Can you handle it?’: Noel pictured in 1996, in the band’s heyday - Peter Wilcock/PA

‘We’re going to be the biggest band in the world. Can you handle it?’: Noel pictured in 1996, in the band’s heyday - Peter Wilcock/PAI remember a time before Oasis, when rock felt moribund, an old genre fading in the dawn of a new electronic and digital age. Pop was splintering into a sci-fi slipstream of techno, jungle, trip hop, big beat and jangly psychedelic indie. Ubiquitous yet unfocussed, all this amorphous noise was strangely easy to ignore. Pop music was everywhere, yet nothing was holding the centre. There were no songs we could all sing together.

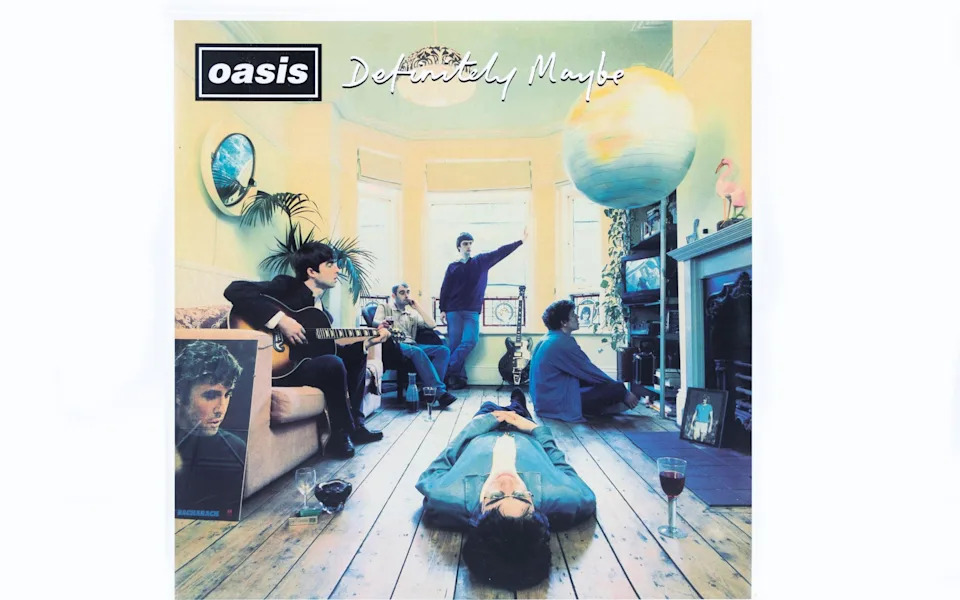

And then boom. In April, 1994, Supersonic was the perfect debut single for the Britpop era, riding in on an insolent riff, sneering vocals and euphoric surrealistic lyrics bound by the assertion that “you can have it all.” It only reached number 31 but it was enough to put Oasis on Top Of The Pops and give Britain a glimpse of its future. A month later, Definitely Maybe became the fastest-selling debut album in UK pop history.

The band’s debut album, Definitely Maybe, became the fastest-selling debut album in UK pop history - Hugh Williamson/Alamy Stock Photo

The band’s debut album, Definitely Maybe, became the fastest-selling debut album in UK pop history - Hugh Williamson/Alamy Stock PhotoWhen we think of the Nineties, the monobrow image of the Gallagher brothers is stamped across the decade. It was surely one of the oddest love affairs in pop history, when a gang of coke-snorting, heavy drinking scallywags were clutched to the collective bosom of the nation, celebrated from Coronation Street to Downing Street whilst waving two fingers at everyone, including each other. Oasis scored 22 consecutive top 10 singles and eight number one albums between 1994 and 2008, with an estimated 75 million record sales.

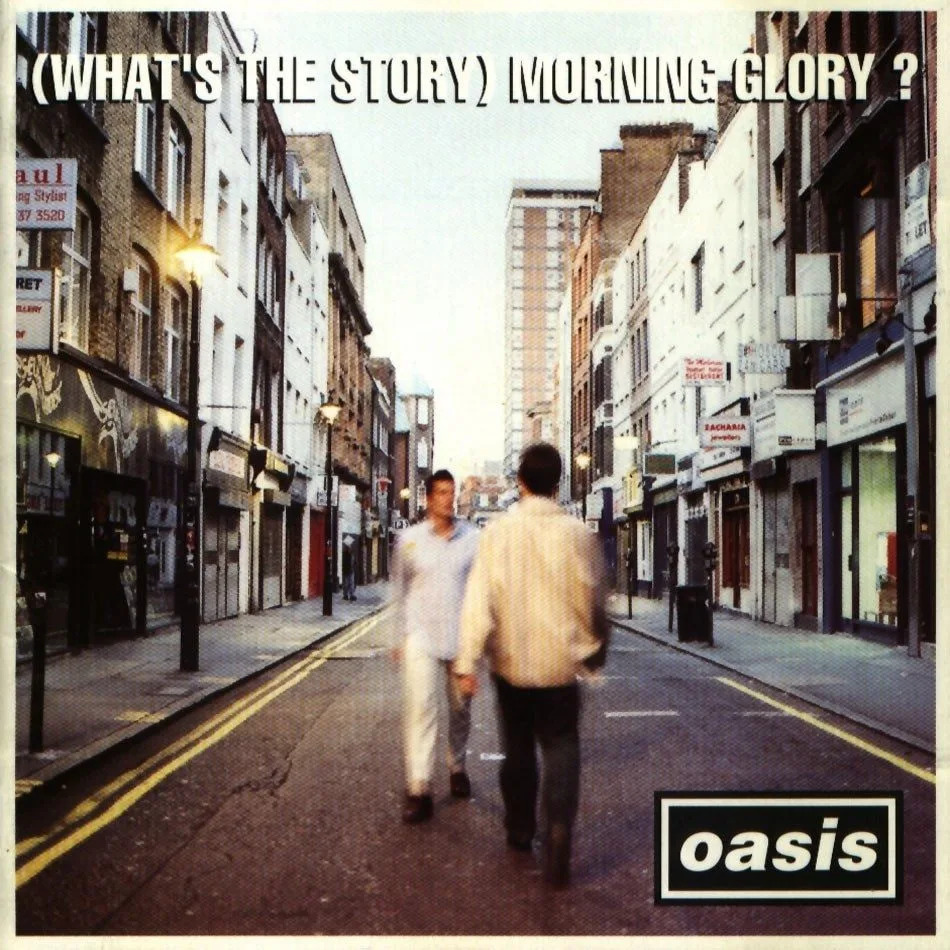

AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R2lekkr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R4lekkr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframeTheir second album, (What’s the Story) Morning Glory was the biggest selling album in the world in 1995. The Gallaghers became the nation’s favourite soap opera. They fought, they swore, they stormed off tours, cancelled gigs and fell out with each other and every original member of the band, and yet achieved something no pop group since the Beatles had done, infusing a whole country with their own self-belief.

Their second album, (What’s the Story) Morning Glory was the biggest selling album in the world in 1995

Their second album, (What’s the Story) Morning Glory was the biggest selling album in the world in 1995Britpop was a great time to be a music journalist. There was a blurring of lines between bands, fans and media. I had many memorable encounters with Oasis, one of the oddest being Liam playing peacemaker when a food fight broke out in a café between members of the Spice Girls and All Saints. The most surreal was driving across San Francisco Golden Great Bridge in a van with U2 and Oasis after a stadium double bill, everyone singing U2’s anthem One.

“I love stadium gigs,” Noel told me, eyes shining. “How many bands can do this? How many?” He proposed a topsy-turvy theory of rock status. “We are the underground and everybody else is the mainstream. Cause they’re all afraid of success!”

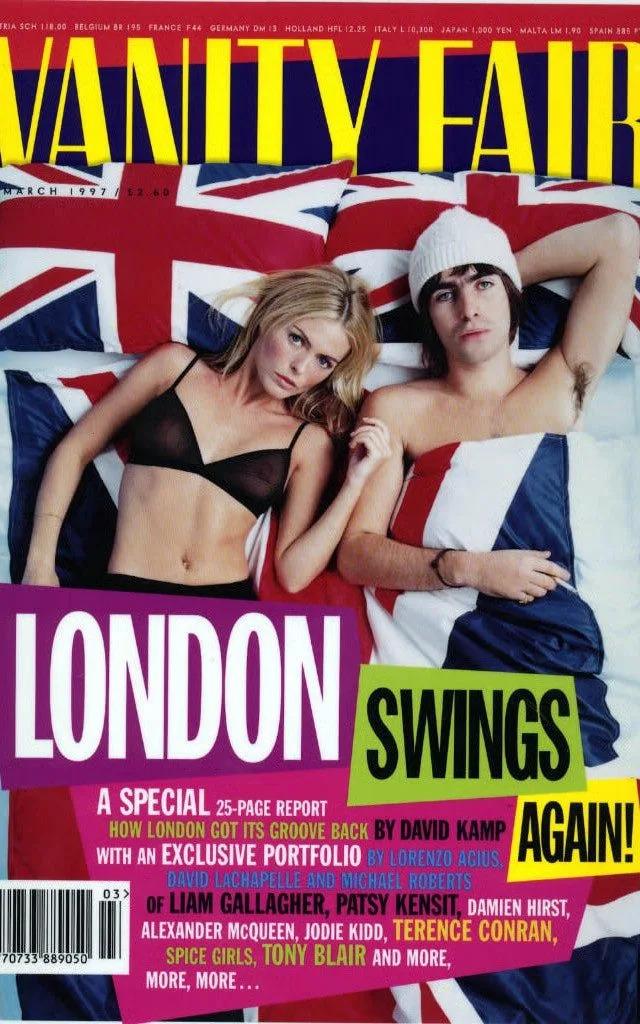

Britain grew heady with notions of musical empires, and Cool Britannia became a briefly triumphalist catchphrase, echoing to the rise of New Labour’s champagne socialism. Into this funnel would pour the Spice Girls, Hugh Grant and Liz Hurley, Baddiel and Skinner, Fantasy Football, Three Lions, Loaded magazine, Katie Price, Vinnie Jones, Lock, Stock And Two Smoking Barrels, Chris Evans, TFI Friday, Robbie Williams, Harry Potter, Damien Hirst’s factory produced spot paintings and a £150,000 price tag on Tracey Emin’s unmade bed. It almost goes without saying that it all ended badly.

Cool Britannia: In March 1997, the cover of Vanity Fair magazine showed Liam Gallagher and Patsy Kensit lying in bed under a Union Jack duvet - PA

Cool Britannia: In March 1997, the cover of Vanity Fair magazine showed Liam Gallagher and Patsy Kensit lying in bed under a Union Jack duvet - PAThe way Oasis swept everything before them, there was an assumption that the sky was the limit. In 1997, third album Be Here Now was initially proclaimed a masterpiece, yet despite notching up six million sales came to be regarded as overworked and hollow. As members left and were replaced, each successive album was scrutinised through a lens of their explosive past and found mysteriously lacking. The critical consensus was that Oasis had lost their way, but it might simply be that the pop zeitgeist moved on, whilst Oasis continued surfing their own mighty wave.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R2uekkr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R4uekkr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframeThey released towering singles throughout the 2000s (Go Let It Out, The Hindu Times, Songbird, Lyla, The Importance of Being Idle, The Shock of the Lightning). Epic ballad Stop Crying Your Heart Out became the soundtrack to the England football team’s quarter final defeat in the World Cup in 2002. There was a generosity of spirit in Oasis that put their critics to shame. When the whole country has its dreams shattered, who would you want to sing to you? Radiohead? S Club 7? Or a bunch of stout hearts from Manchester who could never admit defeat? With the public onside, Oasis continued to play packed stadiums to the bitter end.

And it was bitter, rooted in the antagonistically contrary personalities of the duelling brothers. For a while their sibling conflict had provided much public amusement, with tiffs conducted in a ludicrously comedic language. Noel characterised Liam as “the angriest man you’ll ever meet. He’s like a man with a fork in a world of soup”. Liam branded Noel a “working-class traitor” for the sin of eating tofu. Yet the animosity directed towards each other was counterbalanced by the unity with which they faced the outside world, performing anthems of togetherness such as crowd favourite Acquiesce, duetting “We need each other, we believe in one another.”

The forever feuding Gallagher brothers – pictured here at a gig in 2008 – have traded insults for decades - Fabio Diena / Alamy Stock Photo

The forever feuding Gallagher brothers – pictured here at a gig in 2008 – have traded insults for decades - Fabio Diena / Alamy Stock PhotoUntil they didn’t. Oasis split minutes before a concert in Paris in August 2009, when another trivial argument escalated, guitars were smashed and Noel stormed out. His subsequent statement made it sound like he was suffering from PTSD, insisting “I simply could not go on working with Liam a day longer.”

The Gallagher brothers may be the most psychoanalysed siblings in rock history, yet a tragedy of their relationship is that they have rarely seemed interested in examining it themselves. Noel is the elder by six years, a clever man with a good heart and a lot of humour, whose company I always enjoy. Instinctively opposed to self-analysis, Noel considers songwriting “a calling” and once told me “I don’t aggressively pursue songs, all the great ones just appear.” He recognised recurrent themes, “escape, love and hope” but insisted his songs were not autobiographical. “I write from the perspective that there’s this imaginary person called Noel-and-Liam,” he told me in 2007. “Really, I’m quite a private person and I don’t want anybody to know what’s going on inside my heart.”

AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R34ekkr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R54ekkr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframeFor a rock star of his magnitude, Noel is almost entirely without airs and graces. “I like to think I keep it real,” he said, “and Liam keeps it surreal.” Yet one thing that always baffled me is Noel’s blindness to his volatile brother’s neediness. Was it really so hard to detect in Liam’s provocations a desire for the unforthcoming approval of his older sibling?

It was Liam who first formed Oasis, and Liam who invested Noel’s songs with a charisma you could cut with a knife, a magnetic performer who could dig out emotion in even his brother’s most cryptic lyrics. “When I go on stage I try and eat that microphone,” he told me. “That’s it really. I’m not Jumping Jack Flash. I stand as still as I possibly can. I’m in a bubble, man, singing them songs, trying to blast through people’s souls, change their lives. I’m not thinking about anything except getting the message across. I don’t even know what the f---ing message is! I just wanna blast them with rock and roll.”

I have had some fun times in Liam’s company, but I’ve also been attacked and insulted by him and once endured an interview where he thought it would be amusing not to answer any questions (“I’m not joking, man, I just can’t remember,” was pretty much all I got). But I don’t demand of rock stars that they be sane, normal, well-balanced human beings. Liam and Noel’s furious internal chemistry might be the very definition of a unit greater than the sum of its parts.

Sixteen years after breaking up, Oasis still have 25 million monthly listeners on Spotify, over twice the number of their erstwhile Britpop rivals Blur. Their eight number one studio albums and three major compilations remain regular fixtures of the British charts, collectively amassing 1,824 weeks in the top 75. Wonderwall has clocked up 2.4 billion streams on Spotify, a service that was only launching in the UK when Oasis broke up. According to music data analytics site Chartmetric, Oasis are still ranked in the top 20 British artists in the world, and in the top 10 in the UK itself. It is not unusual to hear spontaneous outbreaks of crowds singing Oasis songs at public gatherings. An impromptu rendition of Don’t Look Back in Anger in St Ann’s Square, Manchester in July 2017 in response to the Manchester Arena bombing was a powerful demonstration of its enduring emotional significance.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R39ekkr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R59ekkr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframeWhat’s fascinating is how much Oasis matter to people too young to remember Britpop. Both Noel (now 58) and Liam (52) have carved out arena-level, chart-topping solo careers, but it is Liam who has really carried the Oasis torch. He played to 170,000 fans across two nights at Knebworth in 2022, a larger audience than Oasis drew in 1996. They certainly weren’t all men of a certain age fishing out bucket hats for one last hurrah. Liam has a near legendary status amongst younger British music lovers, who have been indoctrinated by their parents’ record collections while connecting with his wackily amusing online personality and steadfast refusal to mature beyond the lairy spirit of rock’n’roll. Liam is widely celebrated as The Last Rock Star Standing, a man who delivers every note of every song in a tone that cuts right through the mix and burns to the soul.

Ultimately, it is the songs that have kept Oasis in the ether. Noel may talk down his sophistication as a songwriter, but he has a rare gift: the magic that makes things flow. His songs are not always particularly clever, and are rarely radical or earth-shattering, but there are moments when you hear them and nothing else will do. And that moment has arrived once more.

Broaden your horizons with award-winning British journalism. Try The Telegraph free for 1 month with unlimited access to our award-winning website, exclusive app, money-saving offers and more.