'Ice cube' clouds discovered at the galaxy's center shouldn't exist — and they hint at a recent black hole explosion

When you buy through links on our articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

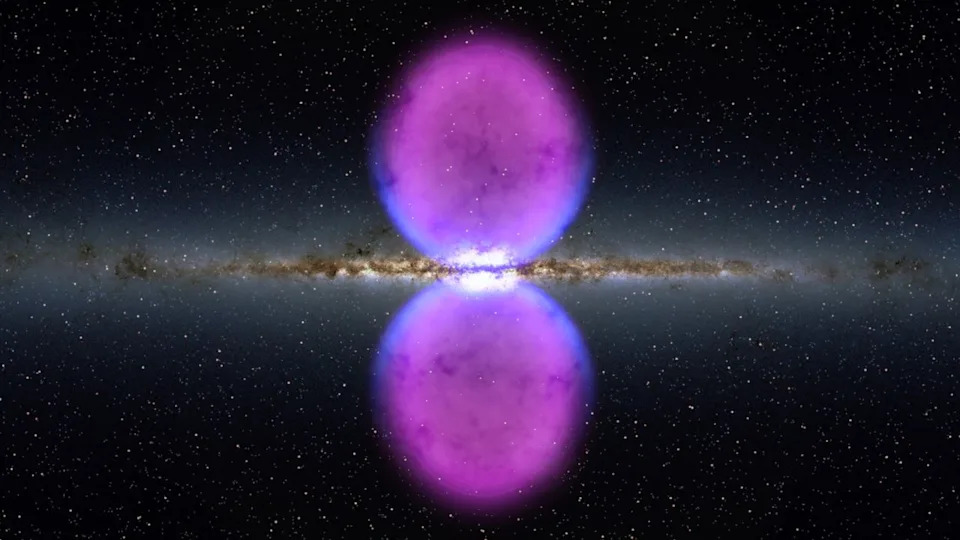

The twin Fermi bubbles (purple) each stretch 25,000 light-years above and below the Milky Way’s center, hinting at an ancient black hole explosion there. | Credit: NASA Goddard

The twin Fermi bubbles (purple) each stretch 25,000 light-years above and below the Milky Way’s center, hinting at an ancient black hole explosion there. | Credit: NASA GoddardTwo of the strangest structures in the galaxy just got even stranger.

Ballooning above and below the Milky Way's center like a massive hourglass, the mysterious Fermi bubbles loom large over our galaxy. These enormous twin orbs of superheated plasma have been gushing out of the galactic center for millions of years. Today, they span some 50,000 light-years from tip to tip, collectively making them half as tall as the Milky Way is long.

Now, scientists studying the perplexing bubbles with the U.S. National Science Foundation Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia have discovered something shocking: Nestled deep within the superhot bubbles are gargantuan clouds of cold hydrogen gas that have inexplicably survived in an extreme environment.

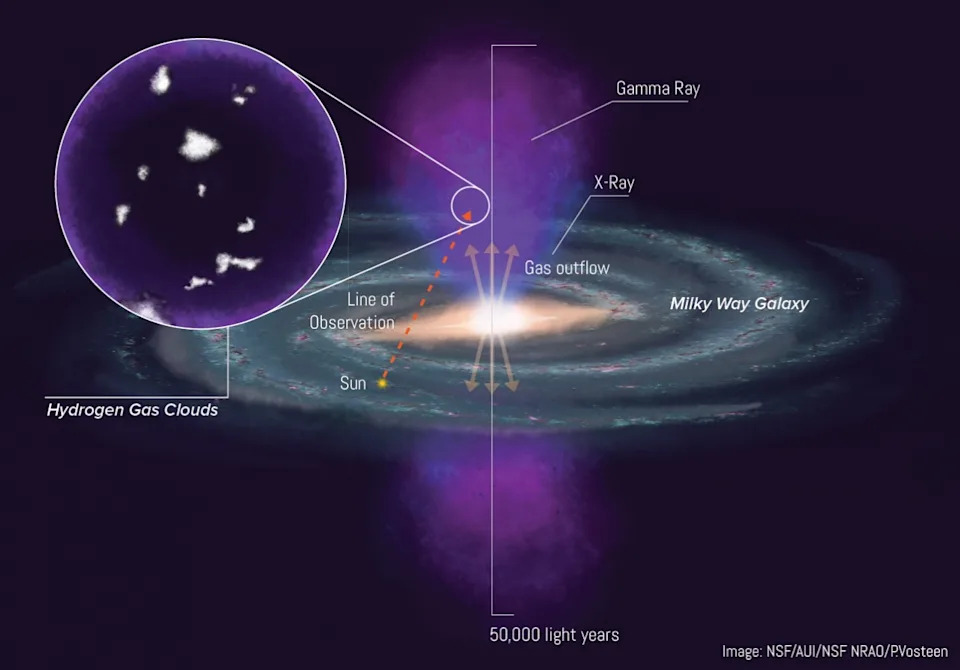

An illustration of the cold hydrogen clouds nested within the Fermi Bubbles. | Credit: NSF/AUI/NSF NRAO/P.Vosteen

An illustration of the cold hydrogen clouds nested within the Fermi Bubbles. | Credit: NSF/AUI/NSF NRAO/P.VosteenAccording to the researchers, these bewildering clouds are likely the remnants of much larger structures that puffed out of the galaxy's center several million years ago.

"Think of it like dropping an ice cube into boiling water: a small one melts quickly, but a larger one lasts longer — even as it dissolves," lead study author Rongmon Bordoloi, an associate professor in the Department of Physics at North Carolina State University, told Live Science in an email. "We believe these clouds may be remnants of much larger structures that are currently being eroded by the galactic wind."

The discovery could indicate that our galaxy's central black hole experienced a violent outburst of matter more recently than previously thought, Bordoloi added. The research describing the clouds was published July 7 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Baffling bubbles

Towering over the galactic center, the Fermi bubbles were discovered in 2010 by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. Despite being comparable to our galaxy in size, the bubbles are visible only in gamma-rays, and they overlap with an equally mysterious X-ray counterpart known as the eROSITA bubbles.

These bubbles are incredibly hot, with the plasma that makes up the Fermi bubbles reaching more than a million kelvins (nearly 2 million degrees Fahrenheit). It's thought that the bubbles are likely the result of an ancient, violent outburst from the Milky Way's central black hole, which spewed twin jets of matter above and below the galactic plane simultaneously, scooping up nearby matter in the process and flinging it outward into space.

Related: Scientists discover rare planet at the edge of the Milky Way, using space-time phenomenon predicted by Einstein

The newly discovered cold hydrogen clouds may be remnants of some of that matter, according to the study authors. Spotted with the Green Bank Telescope, the cold clouds range from about 13 to 91 light-years across, making each one many times larger than our solar system.

However, for those cold clouds to survive in the superhot environment where they were discovered — well within the Fermi bubbles, about 13,000 light-years above the galaxy's center — they must have been significantly larger when they were first swept up into the thrall of the bubbles, Bordoloi said.

RELATED STORIES

—Behold, 'The Beast': Gigantic animal-like plasma plume 13 times wider than Earth hovers over the sun

—Scientists detect most massive black hole merger ever — and it birthed a monster 225 times as massive as the sun

—100 undiscovered galaxies may be orbiting the Milky Way, supercomputer simulations hint

"In principle, these clouds shouldn't have survived this long," he added. "Yet they do exist, which gives us a kind of clock: their survival implies that the black hole at the Milky Way's center erupted just a few million years ago. In cosmic terms, that's a blink of an eye."

This discovery could help solve a major mystery about the Fermi bubbles by significantly constraining how old they are. This age, in turn, hints that our galaxy's monster black hole may experience violent, sporadic outbursts whenever large amounts of material fall into it, with the last one occurring more recently than previously thought. However, the precise schedule of black hole eruptions in our galaxy remains an open question.

"What's clear is that features like the Fermi Bubbles — and more recently, the eROSITA Bubbles — suggest the center of the Milky Way has been much more active in the recent past than we once believed," Bordoloi concluded.