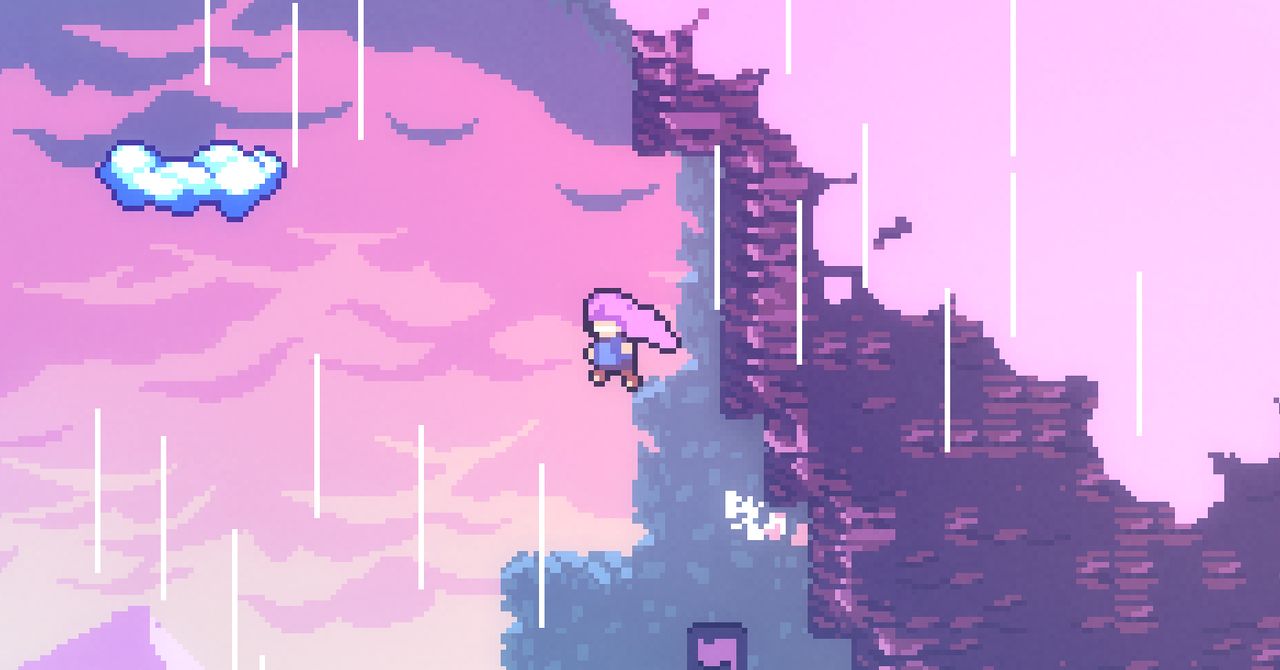

Playing Chucklefish's Eastward is like coming home to a place I've never been before. After its 2018 reveal, I was immediately drawn to the game’s Zelda-like adventure elements, unusually colorful post-apocalyptic narrative, and motley crew of characters. But most of all, I was wowed by its gorgeous, highly detailed environments constructed entirely of pixel art.

"What Eastward does best is create a world that feels like the games we played growing up,” my brother said after the game’s September 2021 release. It joins Extremely OK Games' puzzle-platformer Celeste and Eric Barone's mega-hit farming simulator Stardew Valley (also published by Chucklefish) in a rapidly growing club of video games tapping into nostalgia with high-end pixel art graphics and a retro aesthetic. But while many of these games look like they could have been released on the Super NES or Sega Genesis, they offer more complex graphics and gameplay than those systems could ever handle.

But how does a quirky pixel art game like Eastward make such an impression in an industry obsessed with horsepower and realism? These games see pixel art as more than a relic of the past. It's no longer about technical compromise and limitations, but a flourishing art form inextricably tied to video games. Over the past decade, pixel art has experienced a renaissance thanks to the popularity of indie-developed games like Celeste and Eastward. Twenty-five years after Sony and Nintendo tried to kill it, it's proving popular not just for its nostalgic appeal but as a platform for modern gaming experiences.

4-Pixel Face"Pixel art has a lot of parallels with Impressionism," Pedros Medeiros says from the Vancouver, British Columbia, offices of Extremely OK Games. Medeiros is the visual artist behind indie darling Celeste. His work famously uses blocky, impressionistic pixel art to convey more emotional punch than many AAA games with sky-high budgets and all the cutting-edge technology in the world.

Like the Impressionist paintings of Monet, pixel art asks the player to fill in the blanks with their own experiences, forming a unique personal relationship with the creator. By nature, pixel art is limited by its canvas. Unlike other types of visual art created by paint brush, watercolor pencil, or 3D polygon, pixel art is created one color block (pixel) at a time. And more often than not, the canvas for pixel art is low resolution. Celeste's protagonist, Madeline, doesn't really have a face in the game. "It's just four pixels," Medeiros says. "But players see a face, right? And the face they see is not the same face I see."

I came of age in the 1990s, when Nintendo was blowing minds with 3D adaptations of its Mario and Zelda franchises and Sony was actively suppressing 2D pixel art games on its brand new PlayStation. Despite exceptions like Castlevania: Symphony of the Night and Suikoden II, pixel art's impressionistic relationship with the player was effectively wiped out by creative and corporate ambitions to chase hot tech.

More From Games vibesTake a Closer Look at Deathloop’s Trippy, ’60s-Infused IslandEwan Wilson

vibesTake a Closer Look at Deathloop’s Trippy, ’60s-Infused IslandEwan Wilson yum yumThe Real-Life Quest to Cook All 74 Stardew Valley RecipesMichelle Delgado

yum yumThe Real-Life Quest to Cook All 74 Stardew Valley RecipesMichelle Delgado How To 21 Surprising Things Your Nintendo Switch Can DoJeffrey Van Camp and Eric Ravenscraft

How To 21 Surprising Things Your Nintendo Switch Can DoJeffrey Van Camp and Eric RavenscraftThe indie game boom over the past decade has helped restore pixel art's reputation, says Christina-Antoinette Neofotistou, a pixel artist with decades of experience. "Smaller teams with smaller budgets can produce a game that would command AAA budgets in the ’90s."

Better known as castpixel, Neofotistou is an illustrator, animator, and game developer. She worked on Space Jam: A New Legacy The Game for Warner Brothers—a *Final Fight–*style beat-’em-up with gorgeous pixel art graphics reminiscent of the Game Boy Advance's trademark chunky style.

“Pixel art is, in essence, geometric problemsolving," Neofotistou says. "Pixels, like mosaic tiles, cross-stitches, and weave loom knots, have ideal configurations they ‘like’ to be in.” This is a simple way to describe the intense push-and-pull of an artist trying to solve a puzzle. “I like the magic-trick quality of it—making the viewer go, ‘How did they do that with so few pixels?’”