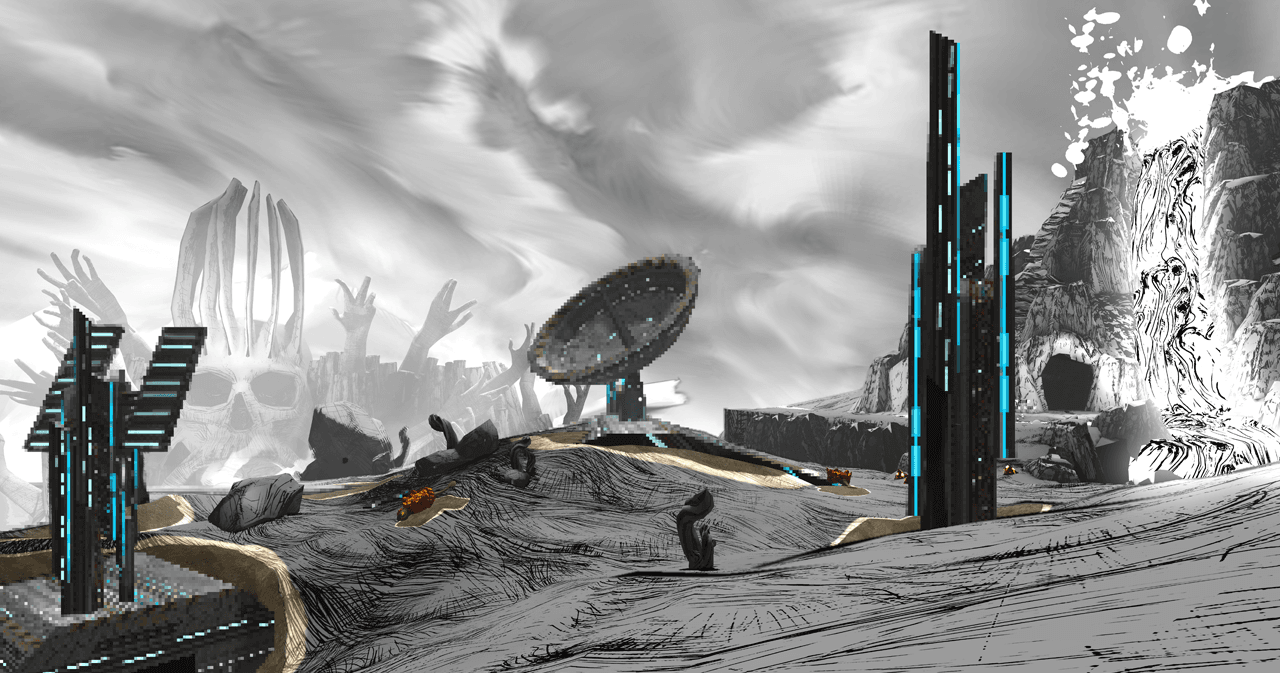

Pony Island begins innocently. Treacly music, art from a '90s flash game aimed at your niece. I press "Start Game." The loading screen "breaks," and before I know it I'm embroiled in a struggle for control of a buggy game experience that might be trying to steal my soul.

Oh, it's one of those games.

Yes, Pony Island, recently released on Steam, is only tenuously about ponies. It's more a game about videogames, a genre that is having something of a moment recently.

Pony Island joins other mid- to high-profile recent indie releases like The Magic Circle, The Beginner's Guide, and Undertale that offer insight into the inner workings of games and gaming. These games use techniques and ideas literary theorists call "metafiction." In her handy 1984 book on the subject, Metafiction: The Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction, lit professor Patricia Waugh defined metafiction as writing which draws attention to itself, to its status and existence as a created piece of art, "in order to pose questions about the relationship between fiction and reality."

Metafiction, when done inelegantly, can feel self-indulgent. Hearing a game talk about itself so eagerly and obviously can prompt ridicule, even contempt, instead of introspection. Some metafictional games certainly can come off as self-important while still having a lot to offer. The best strive to expand their boundaries and give players genuinely thought-provoking questions. They are a springboard for thinking about games, and the world, in new ways. That's the great secret with games about games. They're not about themselves. They're about everything else.

Daniel Mullins gamesRecursive Realities

Daniel Mullins gamesRecursive RealitiesEvery now and then, you glimpse a hand at the corner of the screen while playing Pony Island. It's the player. Not you, but the person you're inhabiting when playing the game. He's trapped, stuck within the closed world of a game-within-a-game, also called Pony Island.

Reality here is slippery, mired in recursion: "You" are the person playing the person playing the game, a strange state that forces you to reflect on your role as both the audience for and participant in the experience. In playing this game, are you the center of this experience, or merely its facilitator? Who's really the player---you, who guides the experience, or the fictitious player who wrestles with the devil in the machine?

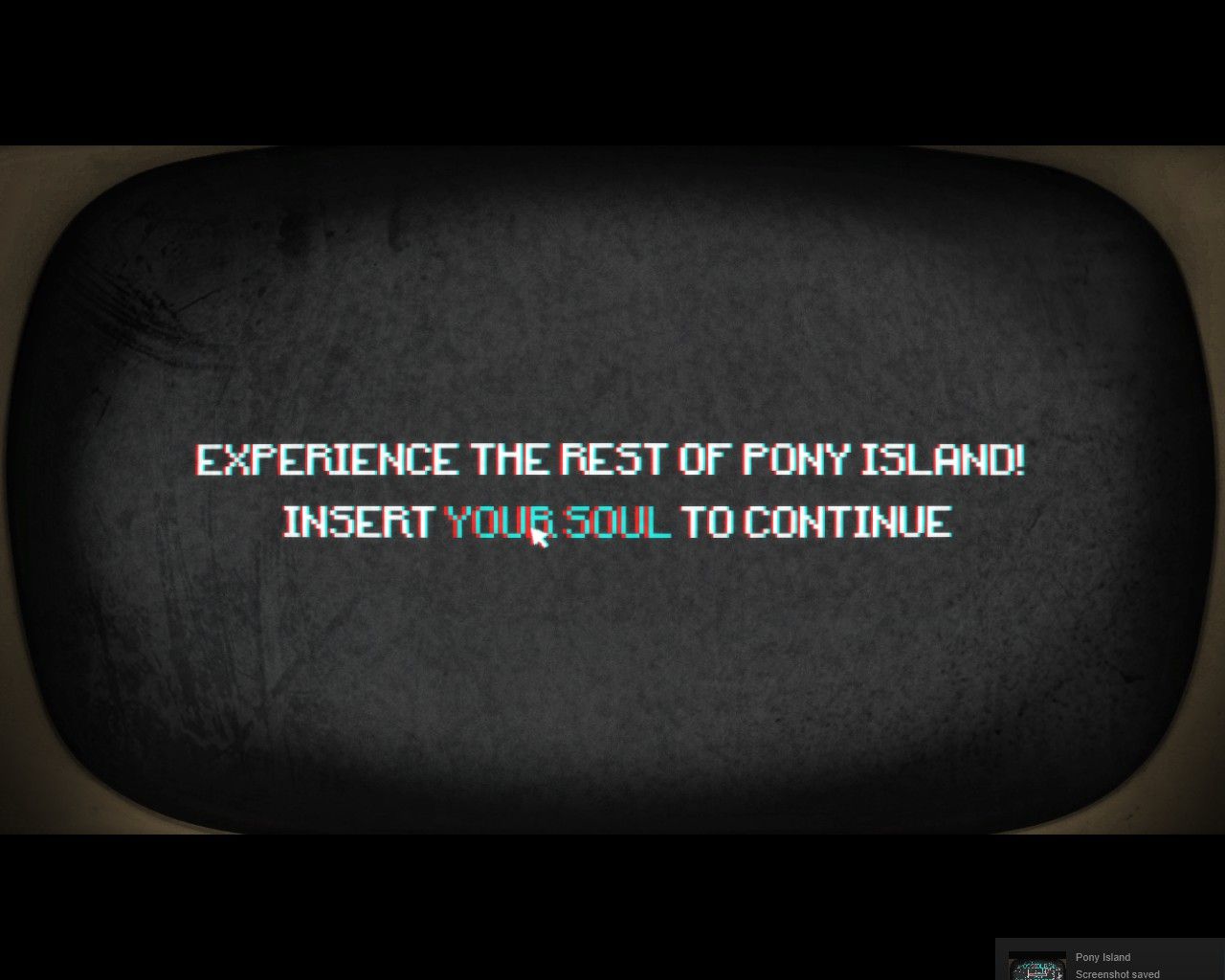

It's a literal devil, too. The game is plagued by the developer of the in-game Pony Island, a Satanic figure who wants to steal your soul through bad design. The game uses this conceit to get at another question metanarrative fiction loves to ask: What's the role of the creator in his own creation?