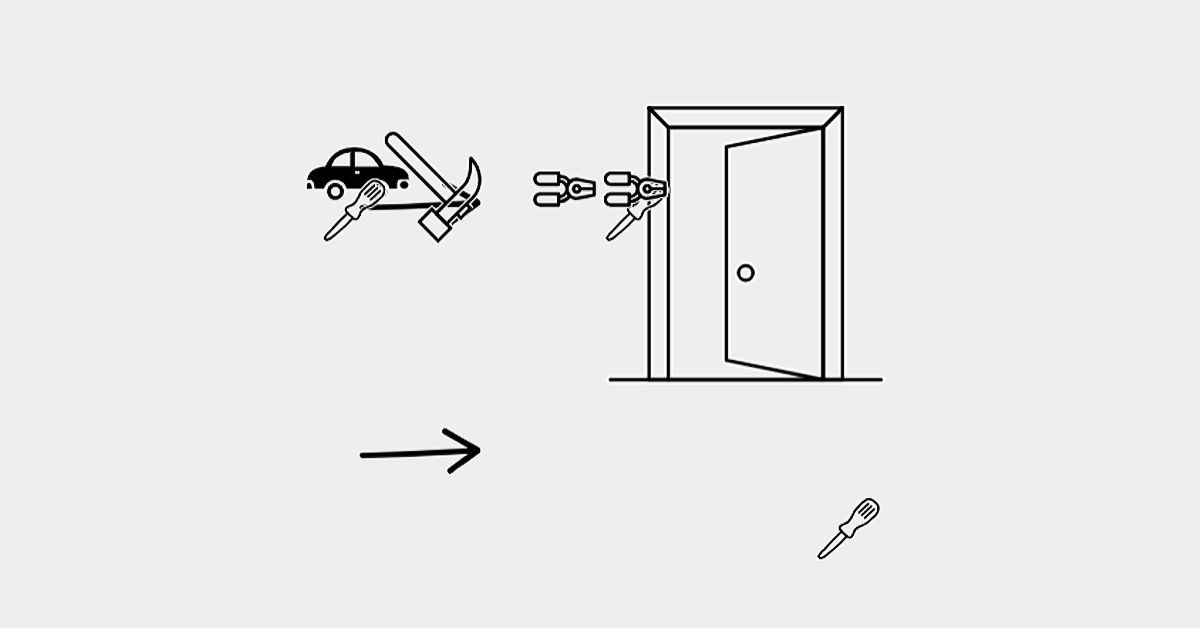

When the arrow appeared next to the birdcage, I finally understood what my partner was trying to say.

The game was a clone of Pictionary—I had to guess the phrase based on a drawing. My partner had initially depicted a duck next to a cage, plus a hand, and a pond. Only after I asked for another drawing and the arrow was added did I realize the hand was “releasing” the duck, not feeding it. “You win!!!” I was told, after typing in the full answer.

There was no prize, but it felt good. My partner felt nothing—because it was a bot. Despite our mutually incompatible hardware and wetware, we’d found shared meaning, of a kind, in a tangle of pixels and characters.

The game, named Iconary, is now available for anyone to play online. If you play, you’ll be contributing to a research project trying to make computers better coworkers and collaborators. You don’t have to play long to see that the bot needs the help. How showing me a cat superimposed with a crucifix was supposed to help signify “laughing in the yard,” is unclear.

Getting computers and humans to play games together isn’t new. It’s been an obsession of some artificial intelligence researchers since the field’s early days in the 1950s. Yet that history is largely one of conquest by machines. Over the decades, computers have progressively beaten human champions at checkers, chess, Go, and in December, the popular strategy videogame StarCraft II.